Cold-water streams are susceptible to a growing problem in rapidly urbanizing areas: thermal loading from heated water that runs off of streets, roofs, and parking lots. A new Dane County, Wisconsin, ordinance is aimed at managing thermal loading, along with other storm water and soil erosion concerns. Using geographic information systems (GIS) and other digital tools, Dane County landowners, developers, and conservationists can now identify land parcels that drain into vulnerable watersheds and predict thermal impacts from runoff. With this information, they can design temperature-reducing features that control thermal loading. This strategy could be used by other communities concerned about the effects of development on their cold-water resources.

Every new residential or commercial development contributes to an often-overlooked environmental impact: heated water that flows into surrounding creeks and rivers. Impervious surfaces — street pavement, parking lots, and rooftops — typically absorb and store more of the sun’s energy than natural surfaces. During summer afternoon thunderstorms, the solar-heated surfaces transfer energy to the water that gathers on them. This heated water quickly moves through drainage ways to nearby streams, with little chance to cool (see figure at left). Accordingly, streams in urbanized watersheds often show increased maximum summer temperatures compared to streams in less-developed areas.

Increased water temperature can have significant impacts on aquatic life, particularly in small cold-water streams. Healthy cold-water streams are able to support cold-water fish (such as trout) that typically require temperatures below 21°C. To protect aquatic life in cold-water streams, a new ordinance in Dane County Wisconsin — the Erosion Control and Stormwater Management Ordinance — includes a “thermal control” section, one of the first legislative attempts in the nation designed to control heated runoff from impervious surfaces. The implementation of the thermal control section of the ordinance offers a model for other communities committed to protecting their cold-water streams from the thermal impacts of urbanization.

Defining Boundaries

Watershed Delineation

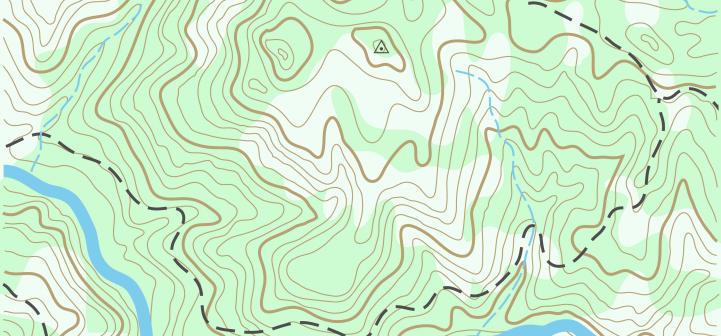

A considerable area in Dane County drains to cold-water streams and is, therefore, affected by the ordinance. The first step in enforcing thermal control regulations is identifying the affected watersheds. Although field hydrologic surveys provide accurate information, the area in question is too vast for on-the-ground surveys. Instead, automated watershed delineation methods use digital elevation models (DEMs) of the areas in question.

DEMs are raster (cell-based) representations of topography; each cell corresponds to an approximately square area on the Earth’s surface. Algorithms determine the direction of water flow for small groups of cells and then aggregate these flow directions to determine the overall drainage patterns for an entire landscape. These derived drainage patterns are used to determine watershed boundaries.

Although automated watershed delineation from a DEM is very effective in high-relief landscapes, low-relief landscapes that have been glaciated — common in southern Wisconsin — are more problematic. Automated methods used to produce DEMs can result in elevation errors that affect derived drainage patterns. For example, DEMs may inaccurately portray sinks — depressions that trap water as it moves over the landscape, preventing it from traveling over the land surface to lakes and streams. Sometimes sinks in a DEM represent legitimate landscape features that are internally drained, rather than errors. Determining which representations are actual sinks and which are errors can pose problems.

Authors: Kathleen Arrington, senior research technologist in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Pennsylvania State University; and Aicardo Roa-Espinosa, Dane County Land Conservation Department. This bulletin was written for RGIS—Great Lakes and the UW-Madison Land Information and Computer Graphics Facility (LICGF). Additional support provided by the USDACooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES). To find this and all other RGISbulletins on-line, visit www.ruralgis.org.